Jim Canning, Glasgow Caledonian University

Supporting Students – First Impressions matter

It is important not to make assumptions when dealing with any student seeking support, especially, for the first time. Their first impressions of you will be the deciding factor on whether they engage with you and with the support that you are providing.

Daily, students contact the Learning Development Centre (LDC), looking for specific academic support. Academic Development Tutors (ADTs), with the appropriate skill set, respond to the students and provide the required academic support. It is a simple model where students have an academic challenge, and they get academic support to overcome it.

However, it has been my experience that students with academic challenges also have other challenges going on in their personal life, which are negatively affecting their mental health, which in turn is negatively affecting their academic performance. Many students keep their personal issues to themselves and do not seek help, particularly young male students. (The GCU School of Computing, Engineering and Built Environment cohort is 90+% male).

Neurodivergent students and students with a disability, are often referred to the LDC for additional support by the GCU Disability Team. ADTs have access to information on the individuals’ condition and the recommended adjustments, prior to a first meeting. However, students can choose not to declare a disability or a neurodivergent condition and seek support from the Learning Development Centre.

This brings me back to the importance of not making assumptions when dealing with any student seeking support, for the first time. Remember, their first impressions of you will be the deciding factor on whether they engage with you and the support that you are providing.

So, how do you make a good first impression, with a student? There are many ways of doing this, but I will share what has worked for me.

Build rapport, to rapidly build trust, let the student know that you, a stranger to them at this point in time, are approachable, and that you can be trusted to listen to their issues, non-judgmentally. Important. To successfully build rapport, you must be genuine and sincere about wanting to help the student.

Listen carefully to what is said, and what is not said, and do not interrupt. When you do speak, do so at the level of language that they are communicating to you with. Do not confuse them with academic jargon. Do not jump to conclusions about what you are told, gently probe to clarify, and understand the issues that they are having.

Gather enough information to make an informed choice on what to do next. You need to decide whether you are the right person to support the student. If not, you should know what support is available and who they could be referred to. If you do refer a student to someone else, take them to that person, and introduce them. Giving a distressed or anxious student a room number and sending them on their way, lacks commitment on your part and any rapport will quickly vanish.

Reframe the issues that the student is having to be not as serious or hopeless as they think. Find positives that can be expanded upon. This can help to break the rumination cycle that they are in. Using metaphors, verbal or visual, can also be effective when reframing something that appears negative into something more positive, more optimistic, more hopeful.

Be flexible. A rigid, ‘one size fits all students’ process, will have a low level of success. The ability to change your approach in an agile manner when you spot an opportunity to make a breakthrough can be beneficial to the student, and very satisfying for you.

The following case study demonstrates building rapport, listening, information gathering, decision making, reframing and flexibility, leading to a successful outcome.

Author: Magdalena Konat

Case Study – Exam Anxiety

Early one morning, during an exam diet, a colleague found a distressed student wandering the corridors and brought them into the LDC office. They tried to calm the student down, unsuccessfully, and was starting to get distressed themselves. Having experience in stress management techniques, I intervened. I invited the student to join me in my part of the office. Using basic rapport building techniques[1], introduced the student to the 7-11 breathing technique[2], and soon the student calmed down enough to have a conversation. I found out that the student had suffered a mental block caused by a panic attack at a previous exam. The panic attack had started just before they had entered the exam room and they fled 10 minutes into the exam. The student had an exam later that day and was extremely anxious that the same thing would happen again. They had been studying hard in preparation but had not been able to sleep the night before.

I found out what room the exam was going to take place and could see that the room was not yet in use. I invited the student to walk over to the room with me and by way of conversation discussed hobbies and pastimes with them – a useful distraction technique to prevent the student ruminating and help gather more information that might be useful. A short distance from the exam room entrance, the student started to panic. I reminded the student to use the 7-11 breathing technique, which worked again. Humour is also a useful tool that can be used to break out of an in-effective behaviour. The student managed to laugh when I pointed out that they were panicking over entering an empty room. The room had approximately two hundred standard single desks, set up ready for the exam. I walked the student into the centre of the room, while they continued to use the breathing technique, and picked a desk for them to sit at. After a few minutes, they had settled down and appeared comfortable. To further reduce their exam room entry anxiety and reinforce their progress, three times, I sent them out of the room and asked them to return to the desk and sit down. By the third attempt, there were no visible panic symptoms, and I made sure to commend them on their progress, highlighting how much progress that they had made in a short time.

The next stage was more challenging as it would test the level of rapport that had been built up, over our brief time together. During the walk over to the exam room, the student had told me that they were very keen on martial arts and had taken part in several competitions in front of large audiences. More importantly, they were comfortable doing this. They had told me that they enjoyed the discipline and rituals of their sport, which gave me an idea. I asked them to talk me through what happens at the start of a competition, and they took me through a formal ritual involving bowing to each corner of the fighting arena and to their competitor. I suggested to the student that the square top of the desk could represent the fighting arena and that they could visualise going through the ritual, bowing to each corner of the arena, and to an imaginary competitor, something representing the exam. The student took a deep breath, closed their eyes for a couple of minutes, and opened them, smiling, totally relaxed. The student had one more trial run, by themselves, while I stood in the corridor, with no panic attacks and looked relaxed and confident.

I arranged to meet them in the LDC, 15 minutes before the exam, and we walked over to the exam room. The student walked confidently into the room and set off for their designated desk. I returned to the LDC at once to ensure that I did not undermine the work that had been done by being seen to wait in the corridor outside the exam room.

Three hours later, a delighted student appeared in the LDC. They had used the breathing technique and the visualisation process and had suffered no panic attacks or mental blocks. They had filled in two additional exam scripts on top of the first script.

The student went on to complete a Masters and has gone on to be very successful in their chosen career.

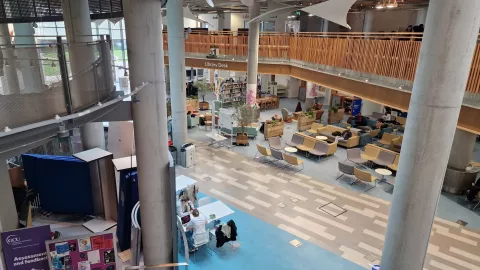

Glasgow Caledonian University - student space, photograph made under the project "Accessible TUL"

Jim Canning is an Academic Development Tutor (ADT) in the Learning Development Centre (ADT) of the School of Computing, Engineering and Built Environment (SCEBE) at Glasgow Caledonian University, in Scotland.

Work experience: 30 years in Industry, ranging from shipbuilding to semiconductor manufacture, with roles in engineering and management. Learned stress management techniques and strategies, to survive and thrive, in a dynamic, high pressure, 24 hours per day, 7 days per week environment. Learned rapport building skills to get the best performance from staff and to resolve interpersonal issues. Two years in the Further Education sector as a lecturer, teaching a variety of subjects from programming to workshop practices to basic aeronautics, followed by 15 years in the Higher Education sector as an Academic Development Tutor.

Learning Development Centres (LDC) and Academic Development Tutors (ADT)

There are three Schools in Glasgow Caledonian University and each one has its own Learning Development Centre, staffed with Academic Development Tutors who have skills and expertise aligned with the needs of each individual School. All the LDC’s provide academic writing support for home and international students, ICT support, advice on study skills and general academic support and guidance. The SCEBE LDC also provides support for Mathematics.

The LDC’s provide support for all students, from those that are encountering difficulties, academically, to those that are performing well but want to improve further. The LDC’s also provide support for students with disabilities or specific learning and teaching needs.

Student support is provided in a variety of ways, online and on-campus, through workshops, small group sessions, one to one sessions, and embedded sessions within taught modules.

The SCEBE LDC has seven ADTs supporting approximately 3,500 students. Four ADTs, one full-time and three part-time, provide support for Academic writing and English for academic purposes. Two ADT’s, one full-time and one part-time, provide support for Mathematics. One full-time ADT provides support for ICT, general study skills, and anything out with academic writing and mathematics.

The LDC has strong links with the GCU Student Wellbeing team and the GCU Disability Team, with students, including neurodivergent students, being referred to the LDC for additional support.

[1] Rapport building can involve physiology, tonality, language, however, a friendly, open, introduction using your first name, to set the level of communication, is a good start.

[2] Slow, rhythmic, diaphragmatic breathing stimulates and tones the vagus nerve which has a significant role in parasympathetic nervous system control. Breathing in for a count of seven followed by breathing out for a count of eleven. The count is not critical, the main point is that the out-breath should be longer than the in-breath.